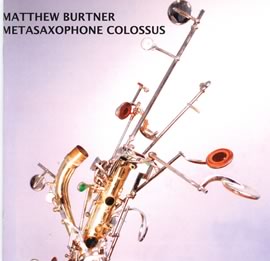

Matthew Burtner: Metasaxophone Colossus

Compact disc, 2004, innova 621; available from innova Recordings, 332 Minnesota Street #E-145, St. Paul, Minnesota 55101, USA; tel (+1) 651-251-2823; fax (+1) 651-291-7978; electronic mail innova@composersforum.org; Web innova.mu/artist1.asp?skuID=199.

Reviewed by Peter V. Swendsen

Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

Released in the fall of 2004, Metasaxophone Colossus is a tour

de force showcase for composer, performer, and instrument-inventor, Matthew

Burtner. It is a compact disc that pays homage to the great Sonny Rollins’s

1956 album, Saxophone Colossus, while bringing together Mr. Burtner’s

primary work from the last few years and thereby providing a bookend to

his 1999 release, Portals of Distortion (innova 526). If you have

been anywhere near the computer music scene in the recent past, you have

likely heard one or more of these memorable pieces performed live by Mr.

Burtner on his elegantly home-brewed Metasaxophone. Anything you give up

in hearing them on CD is quickly accounted for by the delight of having

them collected in one place. At a time when many alternate controllers

and extended instruments surface just long enough for a single piece or

performance, it is a rare luxury for us as listeners and scholars that

Mr. Burtner has developed a legitimate repertoire for his instrument, one

that is both carefully crafted and finely documented on this new CD.

Released in the fall of 2004, Metasaxophone Colossus is a tour

de force showcase for composer, performer, and instrument-inventor, Matthew

Burtner. It is a compact disc that pays homage to the great Sonny Rollins’s

1956 album, Saxophone Colossus, while bringing together Mr. Burtner’s

primary work from the last few years and thereby providing a bookend to

his 1999 release, Portals of Distortion (innova 526). If you have

been anywhere near the computer music scene in the recent past, you have

likely heard one or more of these memorable pieces performed live by Mr.

Burtner on his elegantly home-brewed Metasaxophone. Anything you give up

in hearing them on CD is quickly accounted for by the delight of having

them collected in one place. At a time when many alternate controllers

and extended instruments surface just long enough for a single piece or

performance, it is a rare luxury for us as listeners and scholars that

Mr. Burtner has developed a legitimate repertoire for his instrument, one

that is both carefully crafted and finely documented on this new CD.

The Metasaxophone is an acoustic tenor saxophone retrofitted with an onboard computer microprocessor and an array of sensors of which Adolf Sax himself would be proud. Jazz is typically offered as the ultimate arrival of Sax’s creation, but those of us who play the often-shunned rebel horn of the classical world can appreciate the fact that Mr. Burtner’s work pays homage to the vision and passion of Sax as an inventor, as well as to his computer music likenesses, such as Mr. Burtner’s former teacher, Max Matthews. But anyone who has seen Mr. Burtner play his creation in person knows that the instrument itself is just the beginning of the music produced on it. Mr. Burtner’s playing technique and musical state of mind are fundamentally linked to the Metasax while also being the key factors in the resulting music’s transcendence of mere technological novelty to a state of engaging physicality.

Metasaxophone Colossus was officially launched at a CD release party at The Gravity Lounge in Charlottesville, Virginia, early last fall (2004). Joined by special guests on stage and surrounded by an eager audience comfortably settled in with food and drink to the kind of welcoming setting that would benefit much other electro-acoustic music, Mr. Burtner presented the entirety of his new CD in an impressively unified display of technical and creative energy. While evident in person, it should be made clear here that the compositions on this disc are not for “instrument plus tape” or even “instrument plus electronics.” They are, at least conceptually and usually practically as well, pieces for “instrument plus itself.”

The album’s first track, S-Morphe-S, is a fitting introduction and a highly effective use of physical modeling synthesis. Illustrating Mr. Burtner’s broader reinvention of the saxophone, the instrument in this case is actually not the tenor-based Metasax but rather a hybrid of Mr. Burtner’s soprano horn and a convincing computer model of a Tibetan prayer bowl by physical modeling expert, Stefania Serafin. The piece opens with a sounding of the bowl as percussive key taps set it resonating, and the listener immediately senses his or her location as being inside the bowl itself. Experientially, the piece—as it then begins to traverse a fluttering and shimmering high register—becomes largely about the modulation of the size and shape of the bowl. At its most precise, the piece places the listener in the small object of the bowl itself; at its most expansive, the listener could just as easily be in an enormous mountain bowl with sound reflecting off distant canyon walls.

Delta 2 is an emergent feedback piece, its slow evolution relentlessly leading to a prolonged swell of thick and edgy sound. A cross between minimalist pulsing and Hendrix-inspired screeching, it argues against Mr. Burtner’s program notes that call it the “softer side of the electric sax.” Conversely, I find it intensely charged and almost manic in both procedure and performance. That was certainly the case at the CD release party, where Mr. Burtner was joined for this piece by the wonderful jazz trumpeter, John D’earth. Having begun the piece quietly at opposite ends of the stage, by the end the players were inches from each other, red in the face, and wailing on their horns.

S-Trance-S, the longest track on the CD, is linked by both title and approach to S-Morphe-S. The fundamental difference here is that Ms. Serafin’s physical model is that of a string instead of a bowl. Mr. Burtner bows, plucks, and rubs this virtual instrument with a measured and deliberate pacing throughout the piece, which never quite finds the same frenetic energy as most of its counterparts (as the name suggests). This is a late night piece that one can imagine as the middle 12 minutes of an hours-long improvisation. While its gritty bursts of semi-pitched noise foreshadow the intense din that is Delta 1, it eventually leads the listener peacefully to the disc’s “intermission.”

The intermission music itself—St. Thomas Phase—is a tribute to Sonny Rollins. The only non-real-time piece on the disc, it gathers, retains, and expands enormous energy from the sampled Rollins music, spinning a wash of sound that drifts in and out of phase and rhythmic stability. For the ears, it is the perfect palette-cleansing piece of ginger or scoop of sorbet before digging in to the tasty second half of the album.

Noisegate 67, the first piece written for the Metasaxophone, is a sea of breath, noise, and relentless multiphonic textures in which the acoustic qualities of the horn are at their most raw and powerful. The piece is less successful than its album-mates at conjuring a truly unified meta-instrument, often sounding like a standard tenor sax blowing over a background wash of computer-generated sound. Conceptual differences aside, however, this is a striking piece that would likely prove an accessible starting point for anyone coming from the world of experimental jazz or free improvisation.

Speaking of accessible starting points, Delta 1 will convincingly and unapologetically turn you on or off. This is non-stop sonic assault, though the drums produced by Mr. Burtner’s polyrhythmicon—the same tool used for St. Thomas Phase—are underpowered compared to the blaring electric horn. Flying in the face of Spinal Tap’s “our knobs go up to 11,” this is a piece that only has to be turned up halfway to sound loud.

Relative calm returns with the disc’s final track, Endprint. This piece is scored for nine acoustic saxophones, perhaps suggesting that the acoustic nature of the instrument is what truly endures. Rich with electronic-sounding multiphonics, the piece swims in and out of your head. At the CD release performance I sometimes found its swelling resonances so saturating that I looked around half expecting to see people’s skulls actually bubbling and vibrating. Mr. Burtner, using an approach reminiscent of pieces such as Maggi Payne’s Hum and Hum2, harnesses the power of this “choir of the same instruments” to great effect.

Ironically, the originality and even existence of Metasaxophone Colossus is most likely the result of Mr. Burtner giving up the saxophone for several years earlier in his life, frustrated with the conventional techniques and repertoire it then embodied for him. When he finally returned to it, he did so with a Xenakis-inspired commitment to always forget one’s previous creations and start fresh. That spirit is undeniably evident on this fine disc, which should prove equally inspiring to performers, composers, tinkerers, and inventors, while also challenging and rewarding listeners from a variety of musical backgrounds.