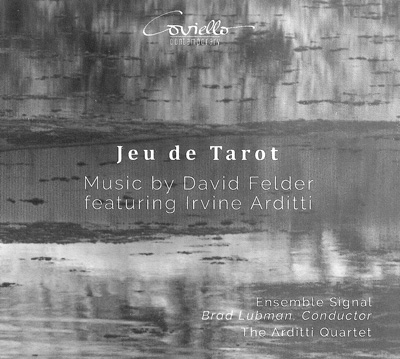

Compact disc, 2019, COV91913, available from Coviello Classics, 21 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3HH, www.coviellomusic.com/.

Reviewed by Ross Feller

Gambier, Ohio, USA

This disc features two, significant,

multi-movement works, as well as a violin solo, by composer David Felder. The

first piece, Jeu de Tarot, is scored

for violin soloist, eleven performers, and electronics. The second piece, Netivot, is for string quartet and

electronics. The presence of virtuoso, violinist Irvine Arditti is felt

throughout this disc, as a soloist alongside an ensemble, as part of a string

quartet, or as an unaccompanied soloist. The two ensemble works will be

reviewed here.

Jeu

de Tarot is based upon seven cards (one per movement) from a tarot deck.

Each is, in a sense, sounded out by the soloist, ensemble, and electronics

part. This piece is chockfull of unexpected sounds, gestures, and combinations

of materials. A keyboard part includes parts for piano, harpsichord, and a MIDI

keyboard, which can, as instructed in the score, be played by two people if

necessary. The MIDI keyboard connects directly to a Max patch. According to the

composer, the electronics part was employed for three reasons: to expand the

keyboard set-up beyond the piano and harpsichord parts, to trigger cues from

the keyboard part itself, and “to expand the tuning world of the piece and to

present pre-made orchestrations – impossible live – of a set of sonic images

related to the characterisitcs that are latent in each of the Tarot cards.”

In The

Juggler, the first movement of Jeu de

Tarot, the initial tempo is marked Dramatic (quarter equal to 60). Given

the meticulously detailed notation employed by the composer the word ‘Dramatic’

becomes almost a tautology. It is impossible to hear the composer’s efforts as

anything but dramatic. This is especially the case in the textures he wrought: sharp

attacks that initiate entire gestural complexes, unstable changes of speed and

dynamics, and chaotic, registral probing that leaves the listener not knowing

what to expect next. These virtuosic materials negotiate a series of ‘sharp

corners’ that keep the listener on their toes.

The

Fool begins with an explosive, violent energy not unlike some of the

work from the Second Viennese School. Subtle, electronic sounds appear in the

background. About two minutes into the piece the texture shifts subtly to one

characterized by a repeated bass tone, a ‘pivot’ axis around which other

instruments revolve. At points it sounds like the materials are coming at you

too fast to comprehend or register, the effect resembling a cross between Brian

Ferneyhough’s concept of “too muchness” and Iannis Xenakis’s stochastic ideals.

Additionally, there is a non-trivial application of spectral principles. This

is music composed by someone who has mastered the art of writing for acoustic

instruments, and knows how to blend sonic colors.

The third movement, High Priestess, opens with a low rumbling sound played by bass

clarinet and contrabass, at a slow pace, with an edgy sense of restlessness. Various

layers move around and evolve at different rates of speed. Some of these share

pitch material, so the effect sounds like layers are duplicated but slowed down

or sped up with respect to material presentation or development. There are also

marked timbral shifts and contrasts.

The

Hermit contains overlapping pitch collections between solo violin part and

the ensemble. The pitch language makes reference to mid-20th century

dissonance, a musical characterization of anguish perhaps. The violin part can

be heard as an expression of the solitary nature of the hermit. About halfway

through, the piece seems to end but is instantly rekindled with a greater level

of dissonance, wherein the clarinet begins to carry more prominence, at times

sounding like it was the violin’s duet partner.

The fifth movement, The Empress, sounds festive, using the full ensemble with bright

timbres, reminiscent of the ensemble writing of Igor Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat. Materials fly by

at a fast rate of speed. There is something like a circus or carnival aspect to

the music, except that the carnival is extremely dark in tone, using repeated and

parallel moving dissonances. One might imagine this movement as a backing track

to one of Hieronymus Bosch’s paintings. About three-fifths of the way through

the piece the materials culminate to a strategically placed pause, which produces

a subtle textural change that eventually coalesces into a sea of trills. There

is also a coda tacked on to the end, similar in scope to the very beginning,

which is cut short by a punctuated attack.

The

Hierophant is also characterized by harsh dissonances. The keyboard part, almost

as a pitched percussion instrument, blends into the background. The dissonances

at times coalesce into late-Romantic gestural and pitch collections that add a

strange feeling of harkening to the mix. The solo violin part soars above the

ensemble, and at other times joins the texture as a participant. The electronics

part plays a more obvious and significant role in this movement.

The seventh and final movement, Moonlight begins with solo violin

glissandi and scratch tones. The ensemble sneaks in to provide some textural

support. The violin continues with cascading materials at very soft dynamic

levels, at times sounding like birdsong as it plays notes in its highest

register. Finally the texture completely thins out, leaving the violin to have

the last word. The electronics part is so well integrated in this movement and

in the piece as a whole, that it is difficult to hear it as a separate part.

Instead it is used in a fused way that effectively bridges the conceptual gap

between electronic and acoustic.

The next work on this disc, Netivot, is written for string quartet,

electronics, and an optional film part. It was composed for and is performed by

the formidable Arditti String Quartet. The title is a Hebrew word for ‘paths.’

According to the liner notes they are to be understood “in a pragmatic sense as

the things that we walk on in order to get somewhere, but also in a spiritual sense

as a way of being on the route to peace and self-fulfillment.” The first two

movements: Devekut and Hitbodedut are named after forms of

prayer as described in the Jewish Kabbalistic practices of Spanish mystic Abraham

Abulafia. They can be considered as “states on the path towards divine

revelation.” The third movement: Pillars

of Clouds and Fire refers to the guideposts that the Israelites followed

while traveling in the desert.

Interestingly, this work’s harmonic

language comes from analyzed vowel formants produced by the voice. Devekut can be described as a sustained,

microtonal, textural portrait. The various dissonances Felder uses produce

different beating combinations that create viscerally shimmering effects. About

three-fourths of the way through this first movement the texture breaks

violently as if the music had suddenly snapped to attention - revealing

electronic resonant trails that were formerly almost unnoticed. The movement

ends shortly thereafter.

Hitbodedut opens with falling

and wailing gestures. The electronics part is more obvious in this movement. For

example, near the one minute mark we hear some noise and granular sounds that

may have been processed samples of pizzicati heard immediately prior in the

string quartet. This is followed with a poignant section featuring harmonics

harmonic sweeps, and octaves, set into extreme ranges. As this section

continues, more noises are added that might make one think of close-up sounds

of the bow or rosin. Whatever the case, they carry a certain visceral weight

that leads one to consider that what is being heard is the inside of a giant string

instrument comprised of the four members of the string quartet, plus electronic

modifications. Even though these materials capture one’s attention they are

also fragmented and distilled by the composer to achieve a level of

unpredictability. The fast pacing of events suggests that objects are passing

by the listener while perhaps on a journey of their own. Elsewhere in the

piece, material fragments are presented and passed around the quartet that are

also diffracted by the electronics part, creating a dynamic kaleidoscope

effect. The movement seems to end on a pessimistic note. Perhaps the prayer

remains unanswered?

For Pillars

of Clouds and Fire, the third, and last, movement, the electronics once

again are used to granularize the texture but in even more obvious ways than

the other movements. Still, the electronics part is for the most part less

present than the string sounds, which creates a well-blended mixture of

acoustic and electronic worlds. This conjures the idea of a heightened sense of

reality, as if one were looking to clouds or fire for direction. The music for

this movement ends after a fadeout of an open fifths chord, which is followed,

oddly by about 30 seconds of silence, perhaps a connection with the optional

film part.

The pieces on this disc represent the

mature work of a composer worth checking out. His ability to deftly blend

acoustic and electronic materials into convincing compositions is worth

exploring.